To everything there is a season, A time for every purpose under heaven: A time to be born, And a time to die; A time to plant, And a time to pluck what is planted; A time to kill, And a time to heal; A time to break down, And a time to build up; A time to weep, And a time to laugh; A time to mourn, And a time to dance; A time to cast away stones, And a time to gather stones; A time to embrace, And a time to refrain from embracing; A time to gain, And a time to lose; A time to keep, And a time to throw away; A time to tear, And a time to sew; A time to keep silence, And a time to speak; A time to love, And a time to hate; A time of war, And a time of peace. Ecclesiastes 3:1-8

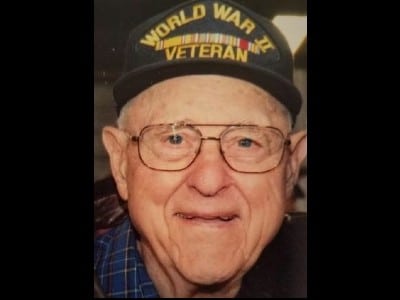

On a December day not long ago, the world lost an amazing man. Joe Meiners was born December 4, 1923, and died December 15, 2019. He was 96.

As I’ve mentioned before, there are times when I’ve been blessed with meeting some truly distinguished people. Joe Meiners is one of them.

Some years ago, my wife and I met Joe after he spoke at a local church about his WWII experiences. After hearing him once, we knew we had stumbled upon a remarkable man. Whenever we heard that he was speaking again in our area, we’d do our best to get there to listen and visit with him.

In 2013 Joe was kind enough to grant me an interview. I usually try to keep these meetings to about 30-45 minutes in length, and sometimes even less. Although I had met Joe only a few times before, he made me feel like a dear friend whom he’d known for decades.

I remember how it seemed that time just flew as we chatted. When I looked down at my recorder, it was flashing red as the battery was dying – I had been listening to Joe for 2-1/2 hours! Yet I knew I’d only scratched the surface.

Joe chuckled as he looked at my blinking recorder. “It’s a wonder it didn’t explode.”

Joe went into the military on March 2, 1943, when he was 19 years old. He went by train to Fort Douglas, Utah. They gave him an aptitude test, and he scored a perfect 100 on the mechanic portion. Then the army took him to Camp Swift in Texas. The war was really heating up, and Joe said they pushed him through a two-year mechanics school in six months.

“Everything we did seemed to be on the run, they were so desperate for men at that time. We were on a 25-mile hike in July. It was so hot that at about the 10-mile mark I passed out from heatstroke. Everyone else went on and left me there on the hot asphalt. After the hike a friend of mine came with a jeep to pick me up. I was dead when he found me. No pulse, nothing. So, he threw the corpse in the back of the jeep and took me to the base hospital. They worked and worked on me. When I came to, the doctor told me that he just knew if they got me back, I’d be brain dead, because I was gone so long. I said, ‘Well doc, I don’t think I’m brain dead,’” Joe laughed.

On December 2, 1943, Joe boarded the Queen Mary in New York and was on the high seas for seven days before he landed at Glasgow Scotland. He went by train to England and worked on all the different types of equipment to get ready for the invasion.

“The first thing I did was drive on the wrong side of the road! I put a guy in the ditch who had a two-horse cart. I remember him shaking his fist at me.”

“The day before the crossing, the day before D-day, they came to me and told me I’d been chosen to be on the initial assault. What they did was put the names of all the mechanics in a steel helmet. And if your name got chosen, you had to go across on the first wave. I said, ‘Well, that is the only drawing I think I’ve ever won, and I didn’t want that one!’”

The rest of Joe’s unit did not go across the channel until eight days later.

“That night before we loaded, there were about 25 guys in this battalion. I said, ‘Let’s have prayer.’ Because none of us knew if we were going to come back or not. ‘Let’s meet over there in the clearing by the river.’ So, there were about 25 guys, but before I could get the prayer started, other guys started coming in from the woods. Before it ended up, we had over 250 guys in the prayer session. I stood there and cried, seeing all those young guys coming in and wanting to pray.

“We loaded on the landing craft, and I had the only truck. It had repair tools on it. The front end of my truck was right against the landing ramp at the front of the boat. We were supposed to have absolute silence going across, and no lighting of cigarettes. Just the low rumbling of the motor of the landing craft. And then I could hear quite a few sobs, guys crying. Going into the unknown. There were 200 men on that landing craft.

“You kind of felt separated from the war a little. You could hear guns going off. Until they let down that ramp. Then all of a sudden you were facing it. They cut loose on us with machine guns. A lot of the guys were killed before they ever got out of the landing craft.”

They had landed on the Utah section of Normandy beach. Joe was 21 years old.

“When the ramp came down, I got out first. I was in about six inches of water over my lap in my truck. I made it to shore and started dodging all the barriers that they put out there. And a lot of bodies, because a few of the landing crafts got there just ahead of us. We got across the beach and up against the sea wall, and out of the view of the Germans. When we got out of the truck, we checked it. There was not one bullet hole in it.

“So, we started gathering our tools to get to work. A two-star general drove up and said; ‘You boys are medics now.”’

“And I said ‘No sir, we’re motor doctors.”’

“No, you’re medics now.”

“Well, I couldn’t argue. He had two stars and I only had two stripes. Then he gave us some bandages and sulfur.

“He pointed his finger at me and said; ‘Now you’re first man on this truck. You have to choose who you pick up and who you leave. You can’t pick up anyone you’re not sure will survive. You can only pick up those you are sure can survive.’”

“That was one of the hardest things I ever did,” Joe stated softly. “So, we started out. There were three guys close by us. The first two I checked out. I thought; well, these guys will be alright if we can get them some help. The third guy, all his insides were lying out on the beach. You could see inside his chest; you could see his heart beating. I knew he was only going to last a few minutes and he’d be gone. So, we picked the two guys up and started to turn away. And he began to cry: ‘Please, please take me too.’ And uh, I uh, I turned away and started to cry myself. I just couldn’t help it. I just uh. And uh, uh, on those first few days on the beach, I uh, we run into that so many times. Some guys would beg you to take them, and others would cuss you out if you didn’t take them. And uh, it was just…uh. Uh, to this day, I still hear those cries. Those cries for help. In my sleep.”

Suffice to say this was a difficult time during our interview. After seventy years, the memory of these sights and sounds obviously still weighed heavily on Joe’s heart. He seemed so fragile at that moment as he reflected back on these experiences.

During the 1970s, the term “post-traumatic stress disorder” (PTSD) began to surface concerning military veterans returning from the Vietnam war. In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association officially recognized the term. Back in WWII, PTSD may have been called shell-shock or soldier’s heart. A very simple definition of a very complex issue is that PTSD occurs when someone encounters a situation where their normal coping mechanism to deal with the crisis is overwhelmed and inadequate to handle the trauma. Flashbacks and nightmares may occur, and the person may become depressed, angry, anxious, fearful, etc. Troubling thoughts may occur long after the traumatic event is over.

Later in our interview, Joe spoke of miraculous rescues and supernatural encounters as he moved away from Normandy Beach and into the interior of the war zone. I plan to write more of Joe’s story in future posts on my site.

But for now, I think it is time to stop.

Having worked with wounded veterans and having family members who were in the military, along with spending time in a few third-world countries where freedom is limited, I tend not to take my freedom for granted. I know there are those who do. Perhaps someday that will change.

But perhaps not.

If you are a veteran reading this, you have my sincerest thanks for your service to our country, and to me personally.

May we take the time to thank a veteran whenever we get opportunity.

And thank you, Joe, for your service.

And thank you for being my friend. May you finally rest in peace.

Joe accepted Christ in 1941. I am so glad he knew the Lord. We’ll meet again – I am sure of it. If you are not sure how you can know Him too, please see Got God?

Hope you have a great day.

Fall Colors IV

Fall Colors IV

Leave a Reply